The thoughts in this section reflect the personal perspective of the CEO, M. David Johnson, based on his interpretation of the data, professional experience, and anecdotal observations.

So, did it work?

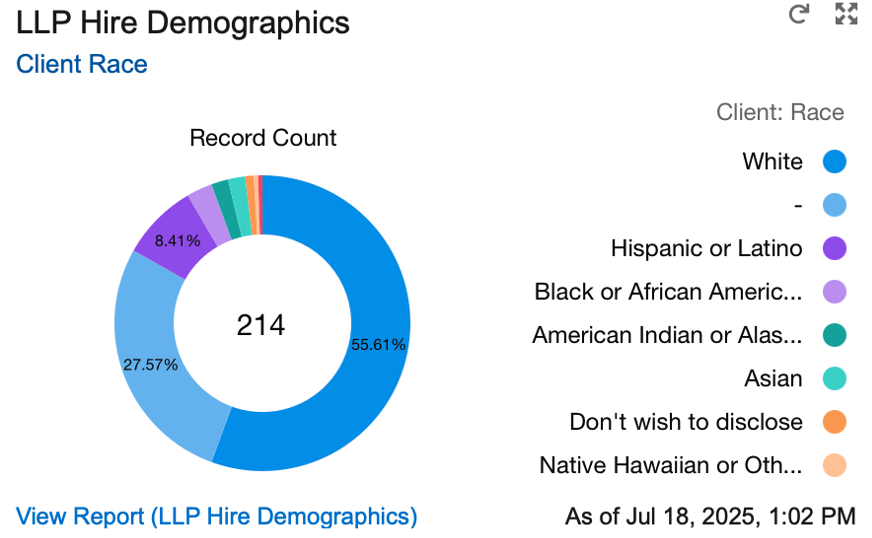

At the highest level, the LLP program is a resounding success. Not only did it crack open a field of law so settled in its ways that change had become virtually impossible—it introduced an entirely new tier of legal service provider. For the first time, professionals without law degrees were authorized to deliver legal services in order to expand access to justice.

The program attracted experienced, energized paralegals who were willing to take a risk: sitting for a bar-like exam, subjecting themselves to ARC scrutiny, and stepping into the courtroom as first chair in family law cases. That took courage. The professionals who embraced this opportunity are trailblazers, and they deserve immense credit.

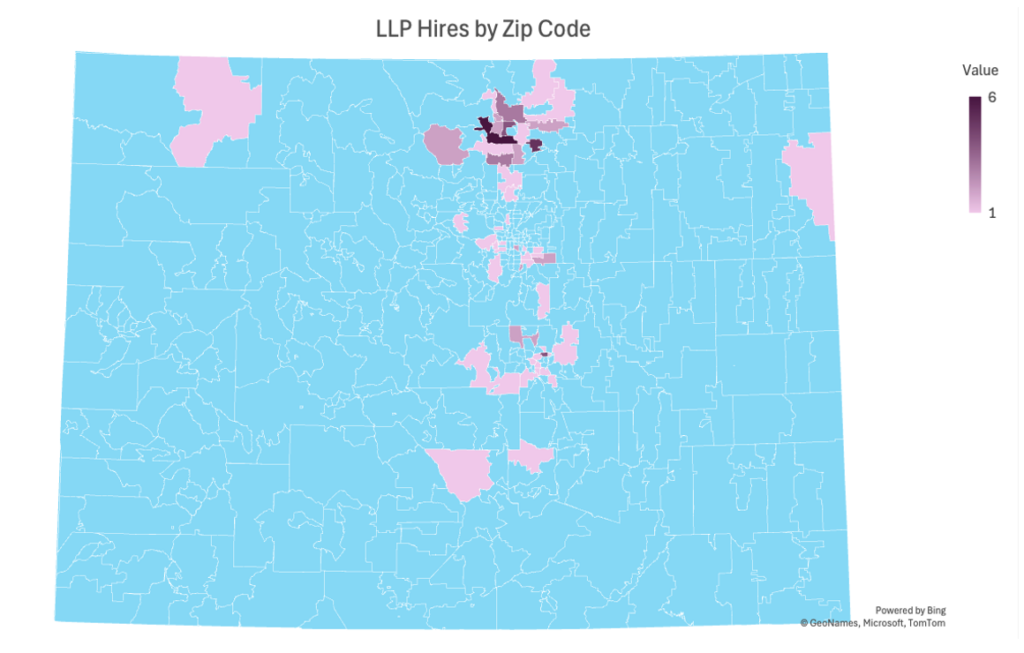

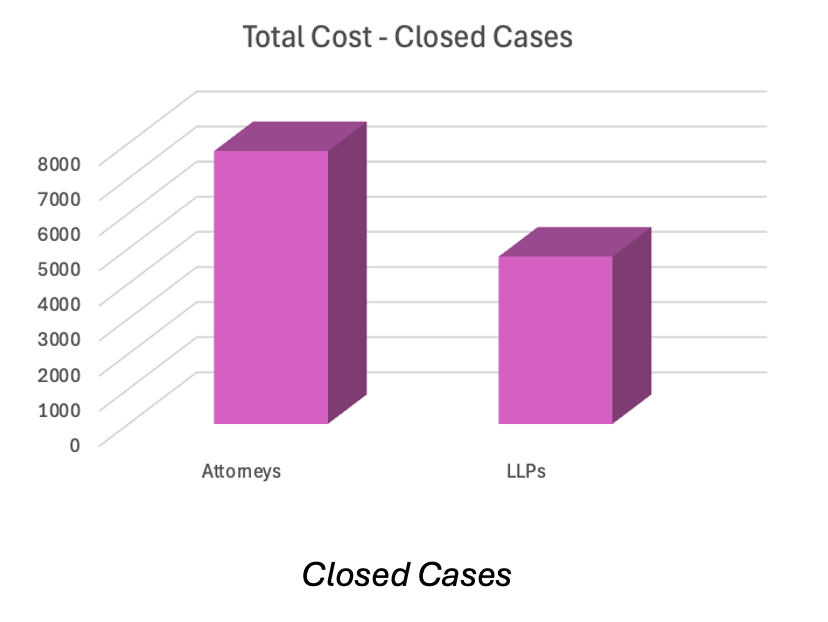

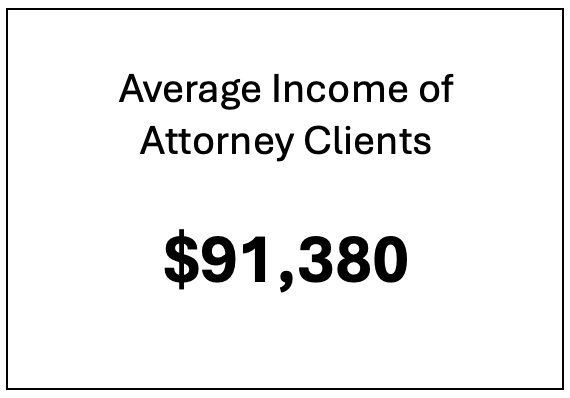

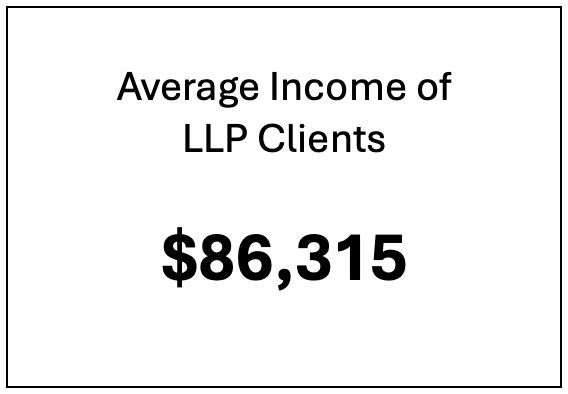

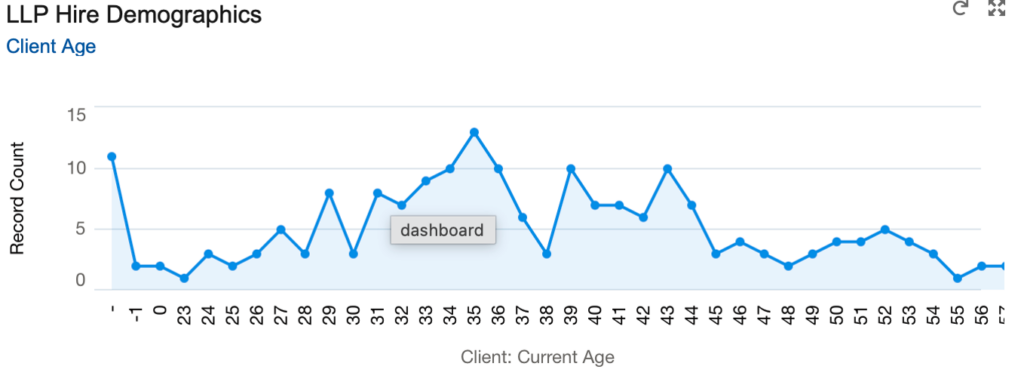

The program has achieved many of its goals—improving access in rural areas, lowering barriers to entry, and reducing the overall cost of legal services. But it’s not without shortcomings. I was impressed by how clearly the geographic data showed a rural preference for LLPs. However, I was disappointed that the program didn’t meaningfully reach lower-income clients. There’s very little difference in the average client income between attorney-led cases and LLP-led cases.

Perhaps the most serious long-term challenge for the LLP program is the cost of investment that law firms must absorb to support LLPs fully. Margins are thinner, and the financial risk is greater.

Consider this: many LLPs were already senior paralegals at the top of firm compensation models. Their pre-LLP billing rates were already relatively high. Now that they’re authorized to practice independently, how much higher can their rates go? How do they compare to, say, a first-year associate? Even if a firm maintains the same ratio of revenue to compensation, overhead, and profit, there’s a ceiling imposed by what the market is willing to pay for an LLP’s hourly rate. That ceiling constrains compensation and, by extension, investment.

More troubling, though, is the Court’s unwillingness to offer any protection for a firm’s investment in growing an LLP’s practice. If a firm trains and supervises an LLP, builds their caseload, and covers the costs of their development—only to have the LLP leave with those clients for a small pay bump or to start their own shop—it’s a losing game. The Justices may say, “them’s the breaks,” but that kind of scenario will end future investment. If it becomes widespread, it could collapse the program altogether. Friends will become enemies.

The truth is, law firms could be the Court’s greatest ally in making the LLP program work. Most of us went to law school out of a sense of purpose—and programs like this speak to that. But we need the economic model to make sense. Let us help you make the program sustainable.

Bottom line? The LLP program is a bold, smart, and necessary innovation. But until the Court allows us to protect our investment in it, I’ll be keeping one hand on my wallet.